I don’t much feel like writing today. I have a headache from staring at my computer all day long, I am tired from being inside my house all day too, yet feel I should be able to last longer than a few hours at my desk. Somehow I get tired here, I don’t know what it is, maybe not having someone to spur me on, maybe it was my hepatitis jab.

I have been out in the village for two days this week, a couple of hundred kms from Dakar, doing a story on a religious group who have started a commune and a clothing business. Their stuff is made from hand-woven cotton in colourful patchwork and stripes. They make hammocks, clothes, wall hangings, bags, shoes. Their things are sold all over Europe and the USA and are well-designed and well-made. I have been buying their clothes for years; all the toubabs in Dakar buy their stuff because despite this country being full of artists and crafts people, very few people have cottoned on to the fact that for art to be interesting it needs to be unique, or at least not a direct copy of someone else’s copy. The products from Maam Samba have hit the mark and the shop is often stampeded by NGO and UN wives in the four wheel drives after the lastest striped baby booties. It is like the Northcote Road, just hotter.

I have been meaning to go to the village for the last year and finally got a BBC and Reuters commission so decided it was time to go. I arrived at the nearest town, Bambay, at nine o’clock on Monday morning. I was immediately hit by the sound of a young boy’s voice singing a religious song to the people inside the car, begging for money. The voice shot right through me. It was perfectly in tune, not like the warblings of most of these boys who are usually under 10 years old, and vibrating perfectly so that it kind of melted through my body. But I lost sight of him in the confusion of finding another taxi to take me to the village, 11 km through the bush, off the main road.

The countryside there is sand and baobab trees and the odd horse and cart rattling through the landscape (see photo of girls collecting firewood for an idea of what it looks like). I arrived at the village, essentially a religious commune, a bright, clean place with rubbish bins (unheard of in Senegal) dotted around, horses tethered under the trees, plants and cactus, bright flowering bougainvillea. The leader of this group is Serigne Babacar (see picture of the man in white a robe), a sixty-something spiritual guide who received a sign whilst in the Pyrenees and returned to the village of his father with his wife, Aisa (a French woman-turned religious devotee).

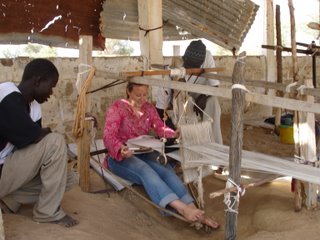

Over twenty years they have built up their commune, and a flourishing clothing business. The cotton is hand-woven by 120 weavers around the 15 villages on long looms, making 100 metres at a time. It is then died either by natural mud dies or chemical dies by local women (see photo of Khady collecting the died cloth on her head), tailored by a team of tailors (see photo), then sent out to its various outlets. The company employs 360 people from the 15 villages around the commune and most of them have only recently come back. Before there was the clothing business the men were forced to go to Dakar to look for work, leaving only children and old people behind. There were no schools, no hospitals, and mostly no water.

Now there are two French schools, one Arabic school, a hospital (see photo of the doctor's daughter Fatim infront of the hospital), a maternity clinic, two deep wells with enough water to grow organic vegetables and cotton and over 300 children going to school. The leader, Serigne Babacar, went from village to village trying to convince the men to let their children do to school. Many of them refused but slowly they have come round to the idea that a French education may not be such a bad thing.

I was deeply impressed by this place. They gave me a room to stay in for two days, food and water and looked after me and let me go around interviewing people without telling me who I should speak to. I found the 5am chanting to the spiritual guide a bit hard to deal with, as well as the PR man telling me to lose 10kg (he later said 2 would be fine), but apart from that it was an amazing experience. The work they have done there is more than anything I have seen either the government or any NGO do in this country. Religion really can be a driving force for development, so it seems.

Part of the success of this business is that this particular sect follows Cheikh Ibra Fall, who was the right hand man of Senegal’s holiest guide Cheikh Amadou Bamba. Ibra Fall’s philosophy was that instead of praying and fasting, one should work hard in the service of those who are praying. “We have time to do all the things that those who pray don’t have time to do,” said one man in the commune. He had been hit by a car in Dakar 17 years ago and come to this village for healing. He is still in a wheelchair but earns a living, and leads a dignified life, by making jewellery.

One of the things that was most noticable about the people at Ndem was that no one called me toubab the whole time I was there. No one tried to make special friends with me, no one looked at me and though "VISA". They were all leading a very normal, but dignified, life, with a job to go to in the morning, on time, and money at the end of it. After seeing how people struggle in the rest of Senegal, how demotivated life without work is, how time has no concept because there's not much to be on time for, it was wonderful to be there.

The man who runs the 120 weavers was a very normal, illiterate but highly skilled, man of about 50. When I asked him how different his life was now that he could stay home and teach his sons how to weave plus earn a good living, his face beamed like the sun. What a difference Senegal would be if people had reliable jobs doing the things they are good at, rather than the useless things that help no one, like standing in the middle isle of a motorway for 10 hours a day selling a cheap Chinese iron that breaks after 3 uses. the phot of the boy crouching on the floor with metres of white cotton stretched out infront of him is this man's 14 year old son.

When I left the village on Wednesday, I made it back to the town where I sat in a dakar-bound car and waited for it to fill up. Across the garage came the voice of the young boy I had heard the first morning and I managed to record him singing. He’ll be going out, along with my report, on the airwaves next week.